12.12.13

12.12.13

Cutting away the Void, is a project with Syrian refugees in Amman. We are making linocut prints that portray members of the Syrian refugee community. At the same time we are teaching anybody interested how to make a linocut themselves.

We have been in Amman for 10 days. During the day we work with the wounded men and women being treated at the House of the Syrian Wounded. In the evenings we run a course for a magnificent group of children, brought to us by a team of highly energetic young Syrian volunteers. Of the children we meet, some are unable to go to school. Those who do go to school come to us late in the evenings as they can only be taught after Jordanian children; the teachers working double shifts. As we get to know one another, each and every person’s shocking story unfolds.

The men are in a ward upstairs. The women live on the ground floor. Their cases are often the most tragic as none of them took up arms and practically none of them were even involved in any demonstrations. Most of the young women have been permanently crippled, their greatest fear being they will never be able to find a husband.

Everybody we met has accepted their fate with remarkable dignity and received us with generosity and gratitude.

What follows is their story.

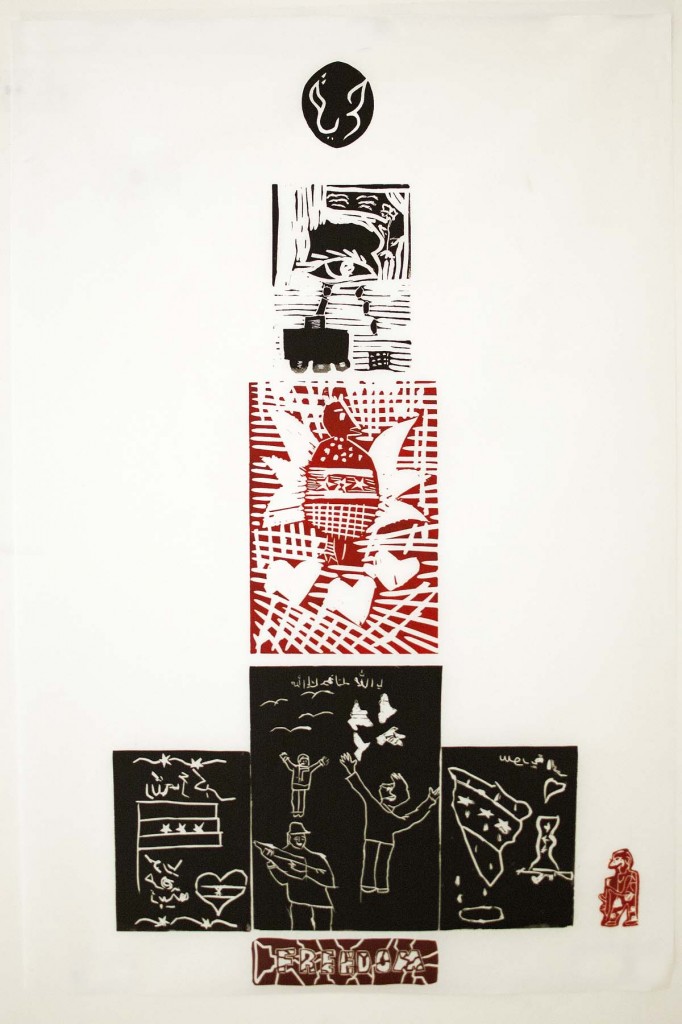

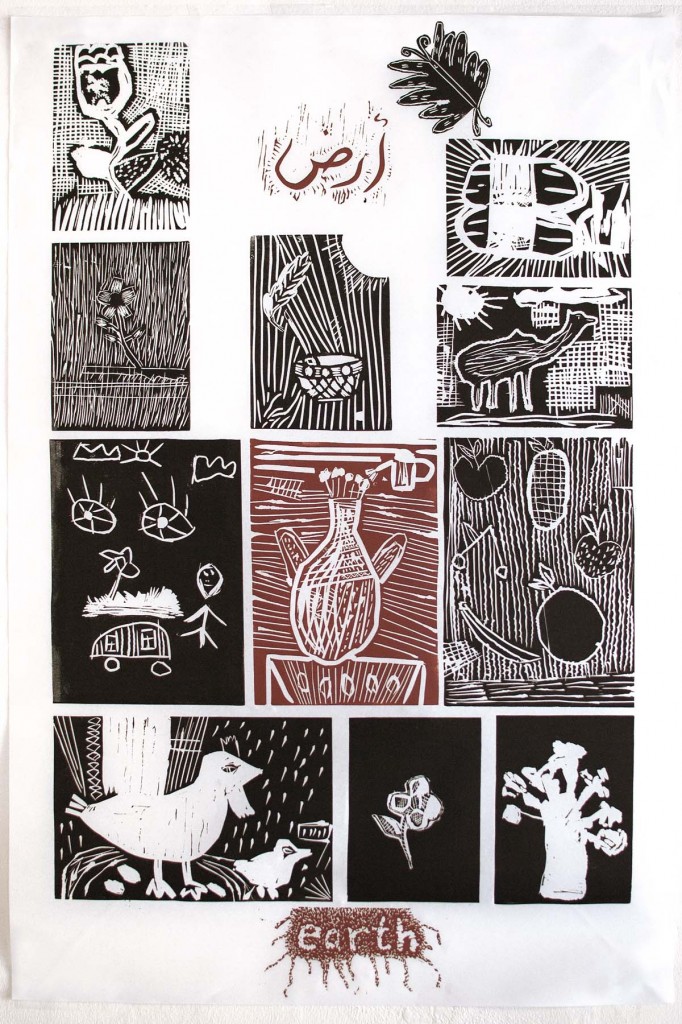

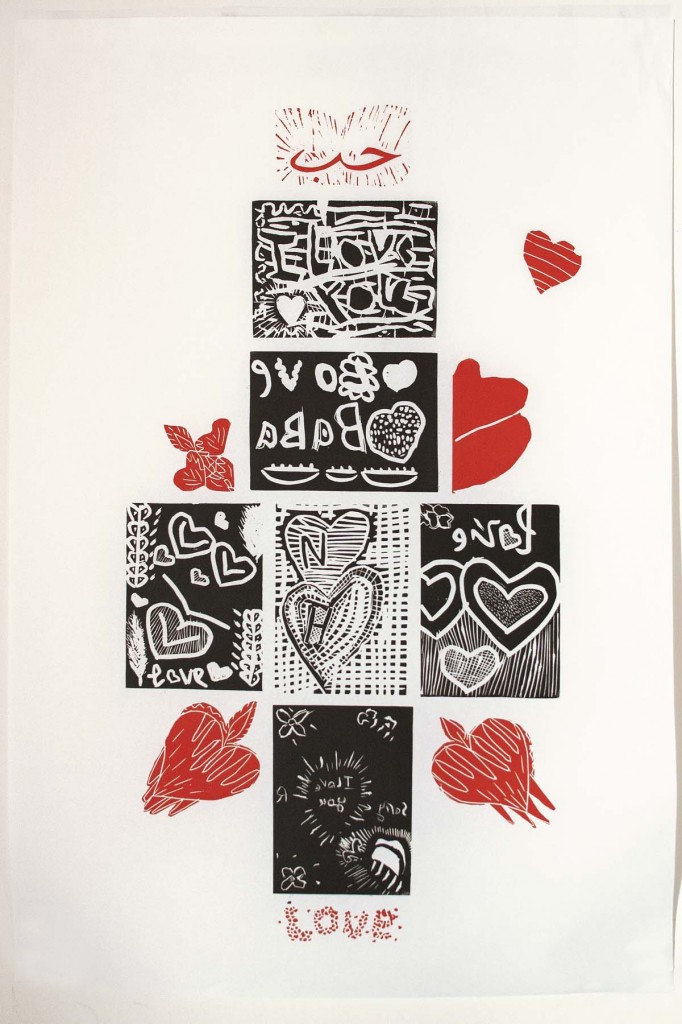

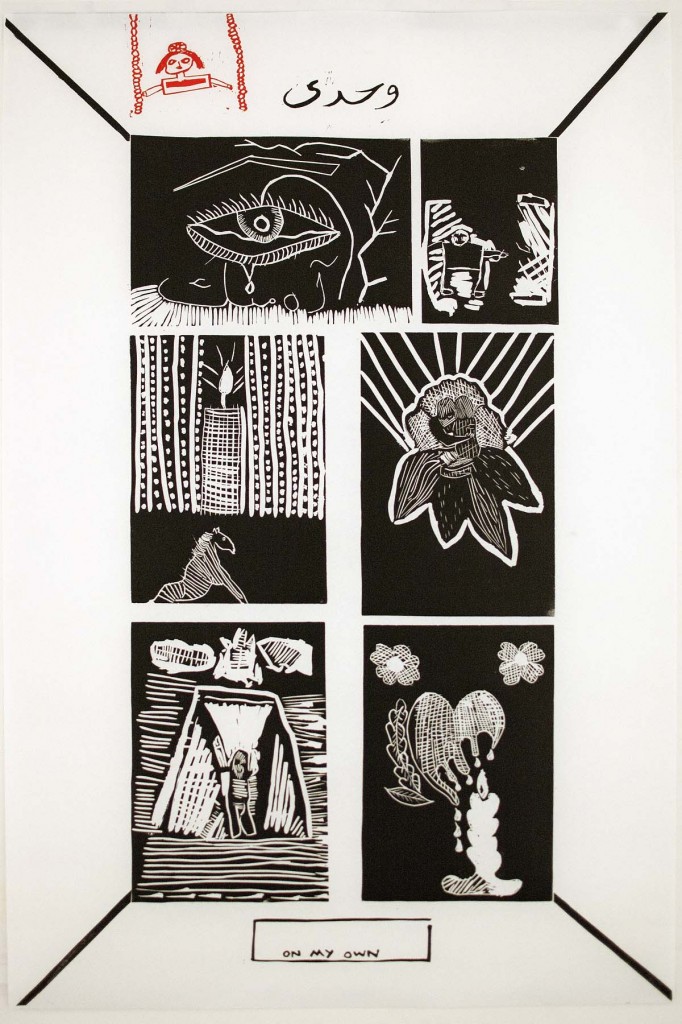

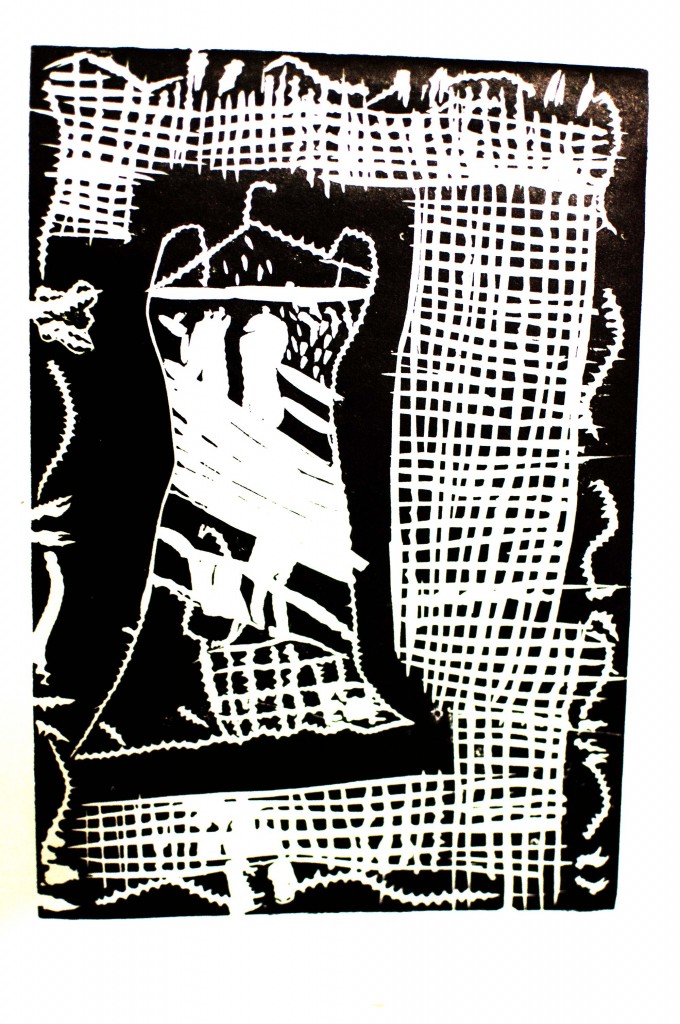

Six broadsheets with images made by the children from refugee families who came to our evening class

-During the first class you made linocuts of the first things that came into your heads. What shall we call this poster; homeland, revolution, nation?

-During the first class you made linocuts of the first things that came into your heads. What shall we call this poster; homeland, revolution, nation?

-No, freedom!

ـ حفرتم هنا في اول جلسة من الورشة اول ما يخطر في ذهنكم. هل نسمي البوستر وطن، امة، ثورة؟

!ـ لا، حرية

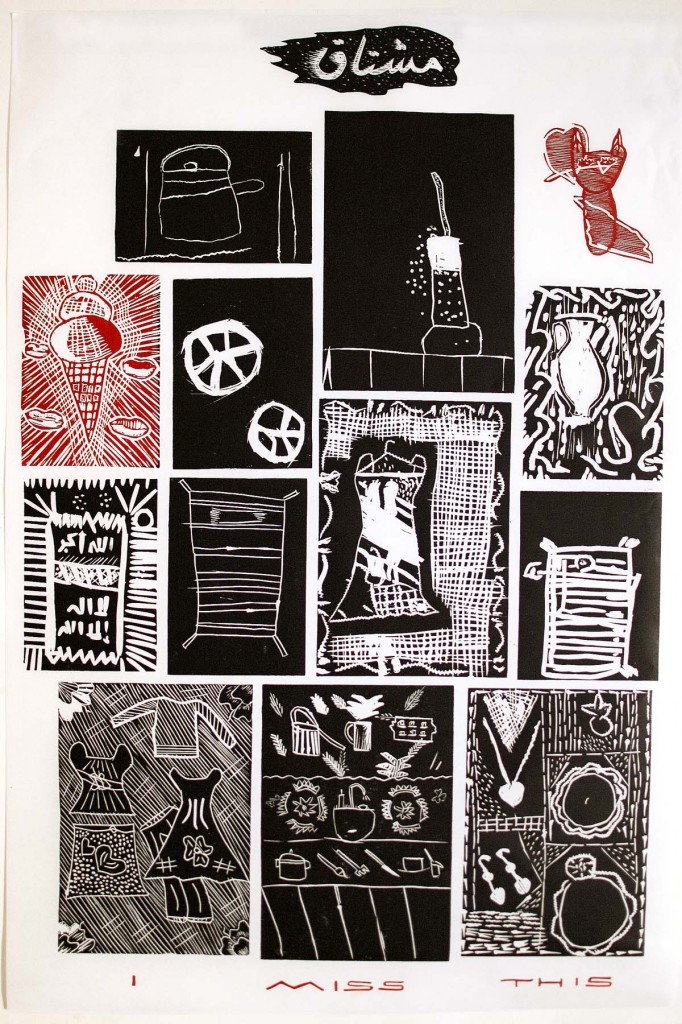

Missing,

Missing,

I miss the details of my room in Syria

my dress, my bed, my cuddly toy, the kettle, my aunt’s prayer mat, my father’s cordless phone

I miss ice cream from Bikdash!

,مشتاق

اشتاق لتفاصيل من غرفتي في سورية

فستاني، سريري، ارنوبي، إبريق الشاي، سجادة صلاة عمتي، طابتي، هاتف لاسلكي ابي

!اشتاق لبوري بوظة من بكداش

What I would take with me if I had to stay alone.

A goal, my lover, a candle, my heart, a swing, a window.

اذا دخلت لغرفة وحدي وبقيت عدة ايام. ما الشي الوحيد الذي احتاجه معي

هدف كرة قدم، عين تبكي، حبيب، شمعة وحصان، قلب وسنبله، ارجوحة….و شبااااااك

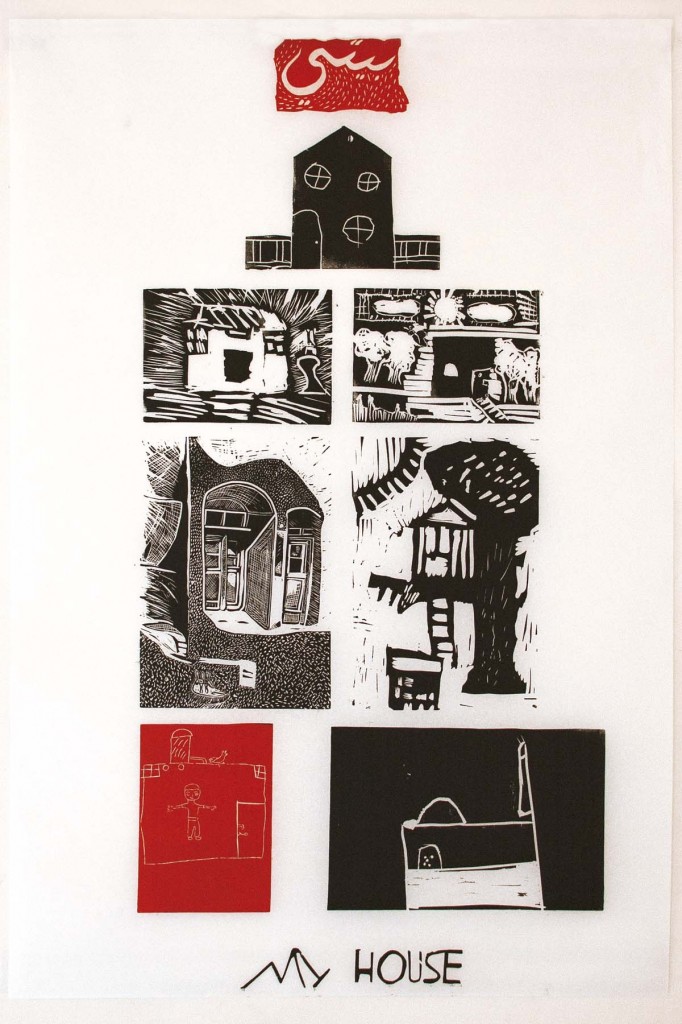

My house, my home, be it in a village or in the city, on the branch of a tree or in an ancient narrow lane, within range of the muazzin’s call to prayer or under the gurgling of the water cistern; my house is where I am me.

My house, my home, be it in a village or in the city, on the branch of a tree or in an ancient narrow lane, within range of the muazzin’s call to prayer or under the gurgling of the water cistern; my house is where I am me.

بيتي، دار في القرية او في المدينة، فوق الشجرة او في الحارات القديمة الضيقة، في صوت اذان الجامع المجاور او صوت خزان المي في اسطوحنا…..بيتي هو بيتي…هو….عندي …انا

Dress, by Rim from Dera’a.

My dress is still in the cupboard in my room. If only I had taken it with me. It’s white and pink with butterflies.

.فستان ، ريم من درعا

.مازال فستاني في خزانة غرفتي. تمنيت لو اخذته معي. هو ابيض و زهري مع فراشات

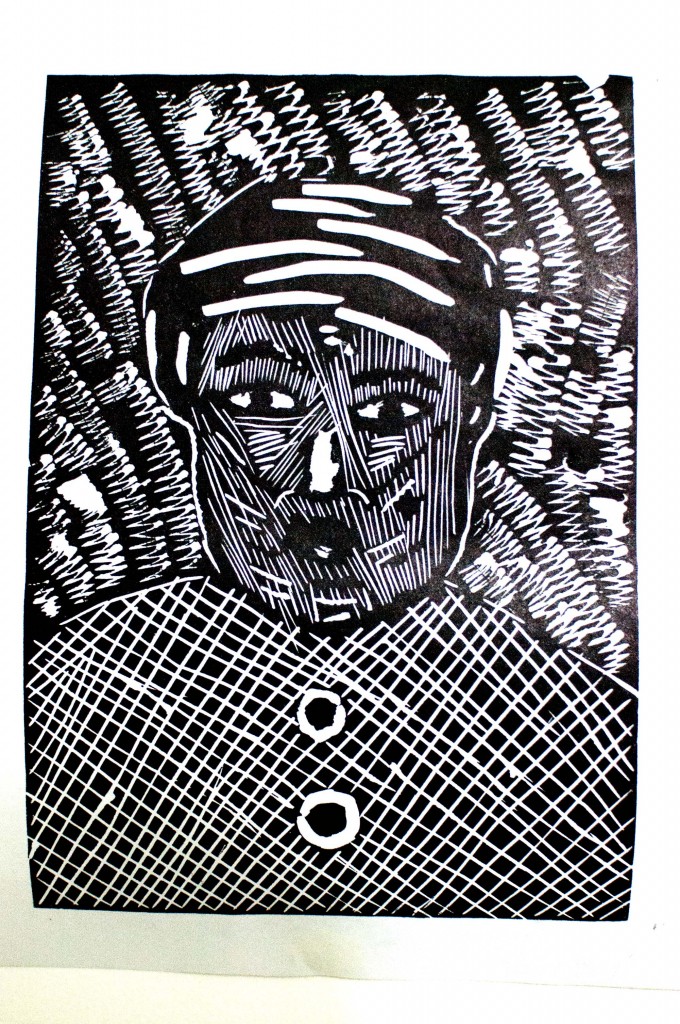

Grandad, by Jannat from the Yarmouk Camp in Damascus.

“I miss my grandfather. I haven’t seen my father for 8 months either. Sometimes my mother cracks up and wants to go and look for him. We try and calm her down. My dad’s a chef, he always used to cook us good food. He stayed at home to protect our home together with the Free Syrian Army. All the men in my family stayed at home.”

جد، جنات من مخيم اليرموك

مشتاقة لجدي

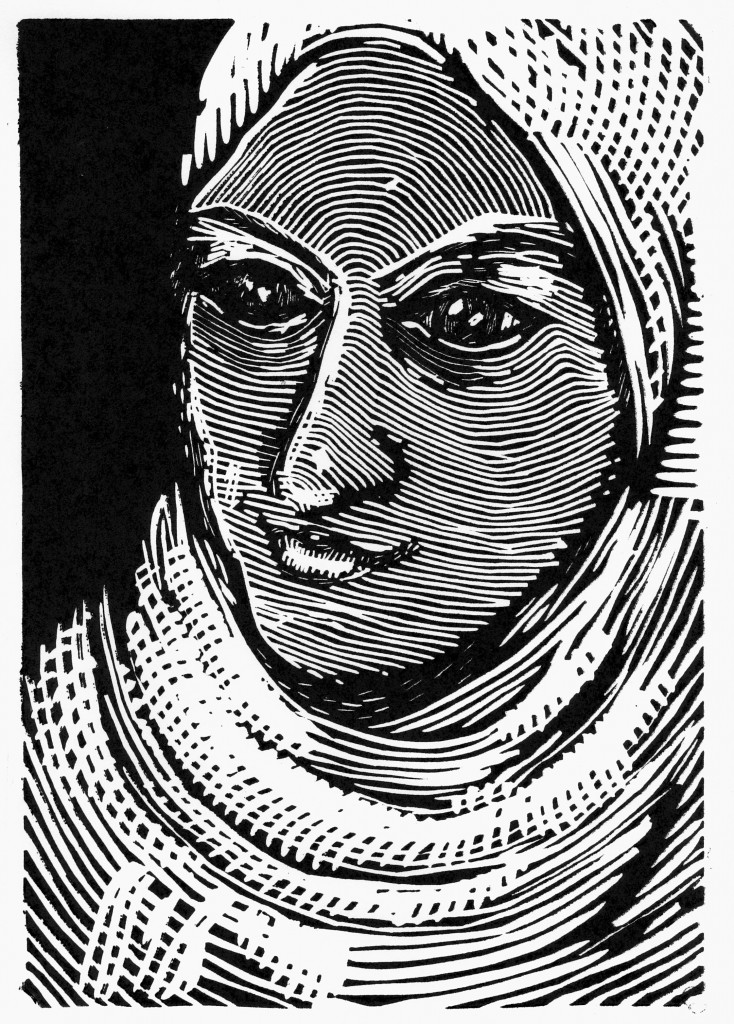

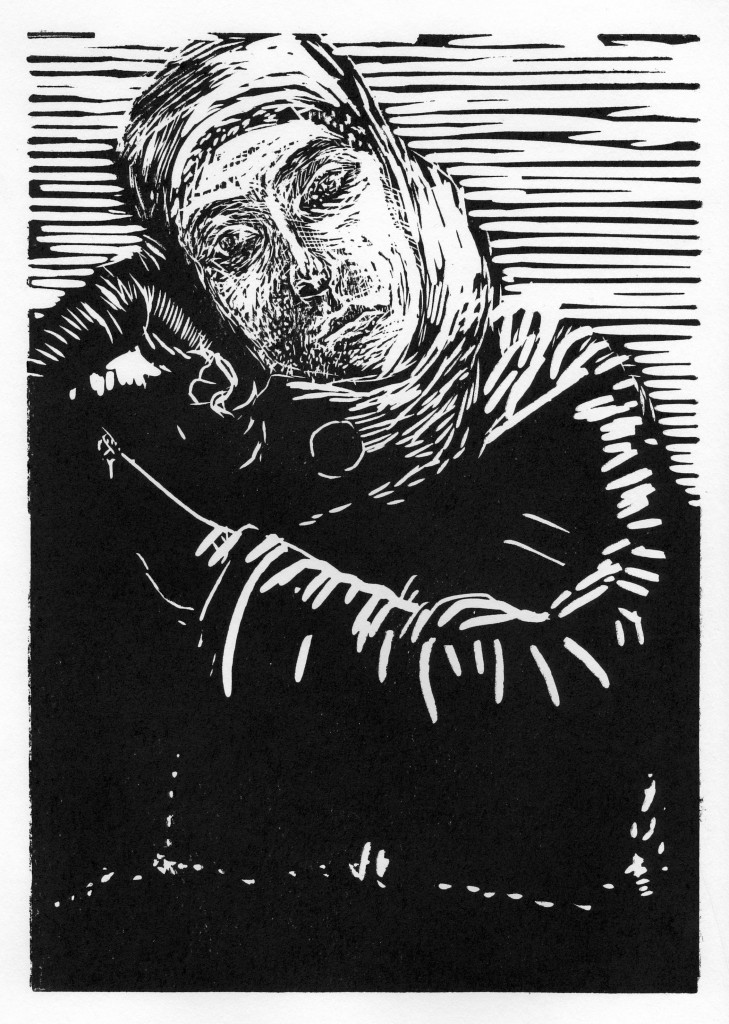

The wounded men and women at Dar al Jerha

“I’m from Dara’a. I married when I was seventeen before finishing school. I have two daughters aged 8 and 11. When I was wounded I was a housewife, my husband was working in Dubai, he’s still there now. My children are with my brother in Jordan.”

“We left our apartment in the town centre because of the bombardments. We went through a checkpoint. We rented another house and stayed there until Da’el was liberated. One day everybody said, ‘tomorrow we will be liberated.’ We got up at 6:00 am and went home. My sister took two of her three children with her and we went to the shop 100 metres away from the house. When we got there the bombing began. I told my sister to hide in a shelter. I went to check the children at home. It tool me an hour to crawl home, there were so many bombs. I reached the third floor and found the children on the stairs. The neighbours said, ‘let’s go down to the cellar.’ There were pillars, we hid behind them because we knew when the army enters a building they spray each room with bullets. I hid the children behind me. There were young men. I was the only woman but I stayed with the children. Later the women arrived and we made a corner for ourselves. I slept on top of the children to protect them. I was hit by a bomb blast. The men didn’t know what was happening because they couldn’t see the shrapnel in my back. We couldn’t call anybody, all telephone networks were dead. I stayed like this, bleeding. People started telling me to say, ‘la illa Allah . . .’ I will never forget this moment. It was like being in front of my own grave. The bombing was unbelievably intense. Somebody dared to go out and find a nurse. God protected him. I don’t know how he came back alive. He couldn’t find anybody. Finally somebody managed to call the pharmacist. He came to our cellar. He was crazy, he risked his life crossing the road with a suitcase on his head for protection. He sewed the wound shut to stop the bleeding and stayed with me all day. They took me to an improvised hospital where I was told they could not remove the shrapnel. They demanded I be sent to Jordan straight away. The activists from Da’el brought me here. There was no space at the first hospital. Some Syrian doctors working there sent me to Dar es Salaam Hospital. There were so many wounded, they had to take somebody out of their bed and put them on the carpet to treat me. I stayed there for three months. The pain gradually left. There were Jordanian officials. Women. They were there to make sure we didn’t escape. One of my brothers tried to get papers for me. There was a mistake. I left with a new name. The hospital director said I would have to go to Zaatari camp. I had a stomach ulcer because of all the medication I was receiving. I was brought to the Moroccan hospital in Zaatari. Within 2 hours I was given the correct medication. My brother gave me his wife’s ID to get me out of Zaatari. I was shaking with fear when we left. I stayed with his family for one week without pain. I hadn’t seen my children for two months. My brother found out about Dar al Jerha (the House for Syrian Wounded).”

“When they called my husband to tell him what happened, he remained silent on the phone for ten minutes. He came to visit me 9 months ago. I see my children once a month. I haven’t seen my husband since. I can’t describe what I felt when the bombing started. When the solders entered our roads everybody hid, they were like barbarians when they came into the shelters. My daughters prayed I wouldn’t die. I tried to calm them down and told them I wouldn’t. I showed one mother how to protect them. I don’t think about the moment I was wounded. I think about how I used to be and how I am now.”

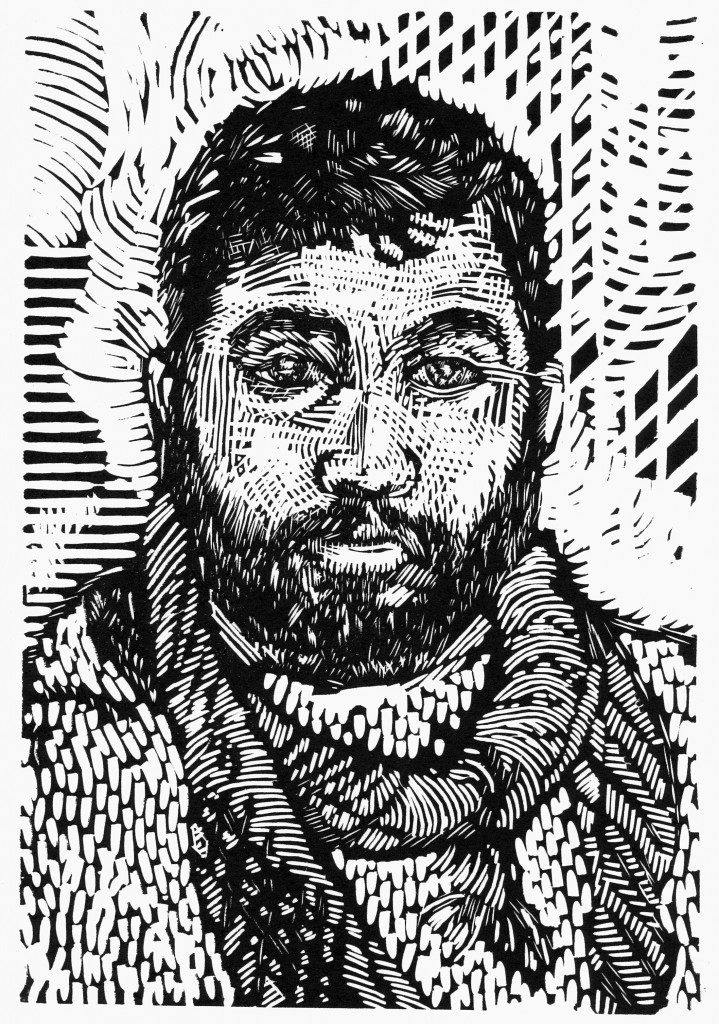

Abu Diab

“I’m 22 years old. I was a mason and laid tiles before I joined the Free Syrian army. Look these are my photos. This is what I used to look like. This is my father, he’s still fighting. I joined one and a half years ago, to defend the earth, it was a natural decision, an obligation. I have no regrets. It is a divine cause. I made a sacrifice for God.”

“We wanted to try and drive the national Army out of a military area. I received a bullet in my back which went through my spine.”

“The most important thing is to know that the Syrian people have suffered a great injustice. We need help from the outside world.”

“With the grace of God things will slowly get better. I think we need to get rid of the Shia and the fire worshippers. . . Sure, there never used to be a problem but if my Shiite neighbour now carries a weapon to use against me I have to protect myself.”

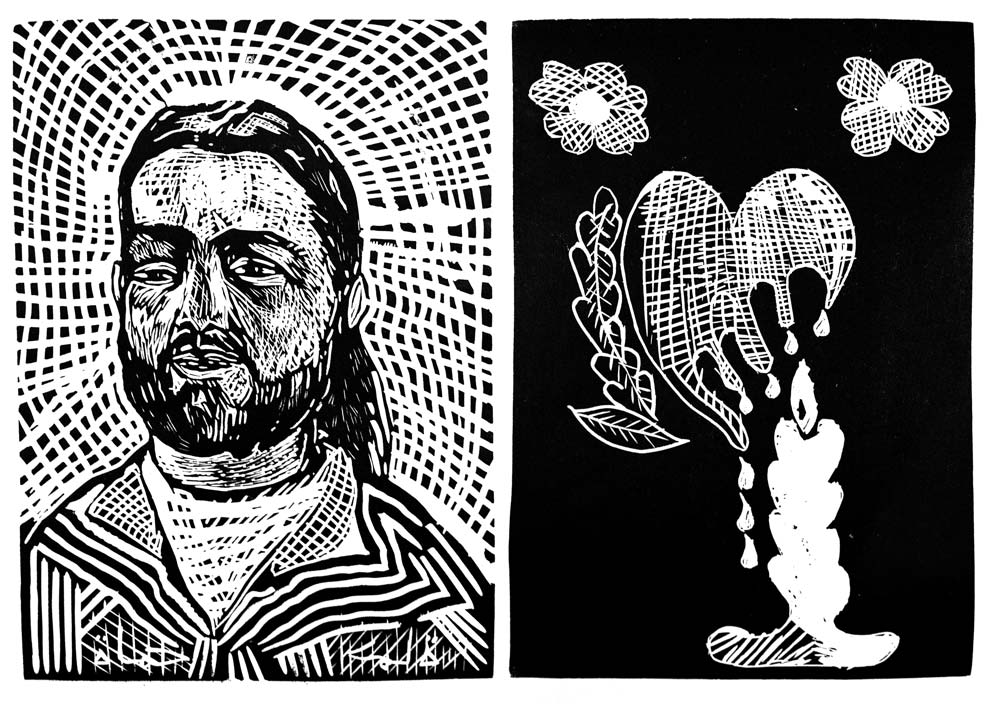

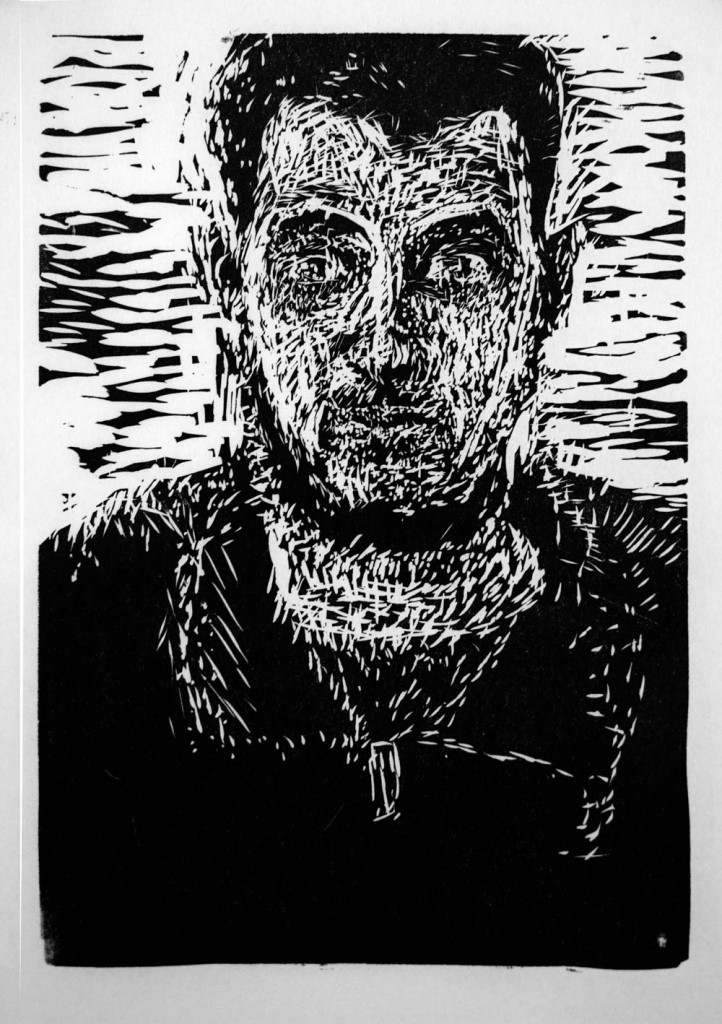

Rabia’

“I’m from Hama. I was in a big demonstration nearly two years ago. ‘The Friday of the Children of Freedom.’ People were coming from all directions. The army were hidden in the park. They had closed off our escape route by welding shut the steel gates. My friend was shot in the head and in the stomach. I wanted to carry him away he was one of my best friends. He died four days later. They were shooting at us from the side and behind. Another friend was shot in the head. I went to get him and was shot with an exploding bullet. I lost my kidneys and most of my intestines. They took me to a private hospital. The public hospitals aren’t allowed to treat the wounded from the demonstrations. There were many wounded there. They left me for many hours and could only do an emergency operation. They took out my kidneys. Then I had to go home. Nobody would treat me anymore. They said it would be a waste of time as I was going to die anyway. I was later taken to one of the public hospitals. I said I was injured in a car accident, otherwise they wouldn’t treat me. A doctor there was helping us and told the officials I needed an operation in Jordan. That is how I came here.”

“I’m Odham from Dera.’ I’m Jeish Hur, (Free Syrian Army.) Put that on my portrait!

I want this picture for my habibty, (my love). Just do it from the waist up, not the wheelchair or the wounds. If she sees me like this she won’t be able to take it. Just write ‘Odham from Dera” under the portrait.”

Bara

Bara

How did you know I’m from Dara’? I didn’t tell you.

Guess how old I am?

18! You think I’m 18! I’m 14!

You made me look like an old woman.

Bashar

“Draw my portrait, I’m going back to Douma. My father is still there, working as a doctor.

A lot of people tell me I should change my name. Why? It’s my personality that counts.

I fought with the Free Syrian Army. You think I should be against arms because of the state I’m in now? I don’t regret my condition. I managed to give the national Army lots of trouble before I was wounded. It was worth it.”

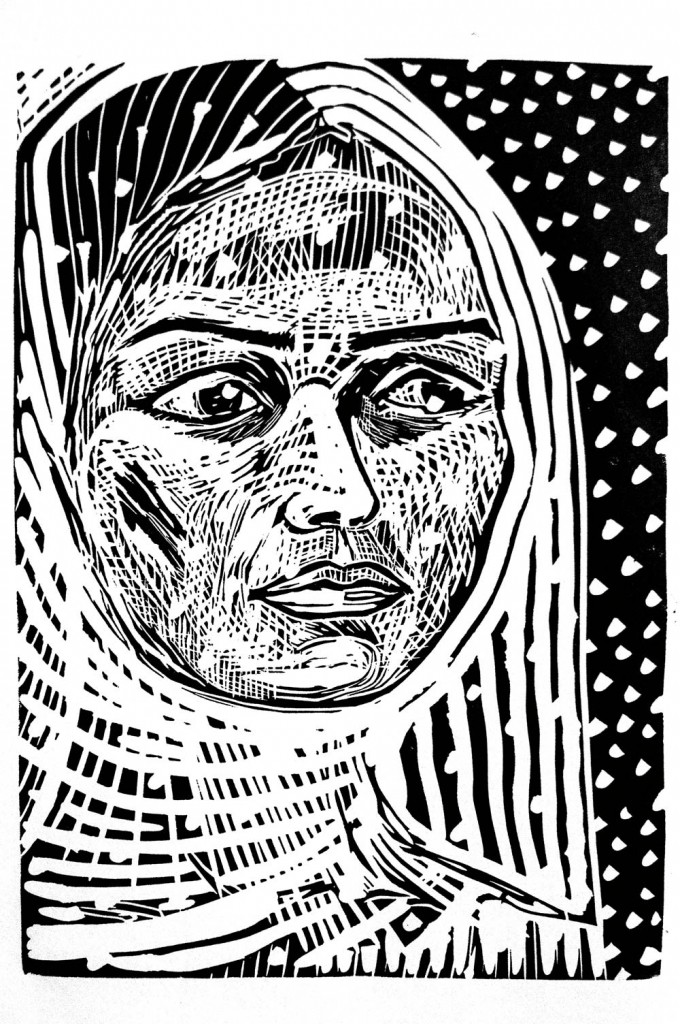

Lubna

“I went out in the morning to catch a microbus, to go shopping. Somebody started shooting at us from a rooftop. Everybody in the bus was killed except me. A bullet entered my back and came out through my left breast after going through one of my lungs. I lay bleeding for hours. Nobody dared come out to help for fear they would also be shot at. Eventually I was taken to a hospital in Dara’ where I was given emergency treatment. I spent two months in hospitals in Dara’ before the Free Syrian Army brought me to Amman. My uncle was in the National Syrian Army but when he saw what they were doing he deserted and joined the revolution.

I had been married for 6 months. My husband who is still in the National Syrian Army came to visit me in hospital. At that point I still had to wear diapers. I am paralysed from the waist down. When he saw the state I was in, he asked if the damage was permanent. He said under these circumstances I could not remain his wife and divorced me.”

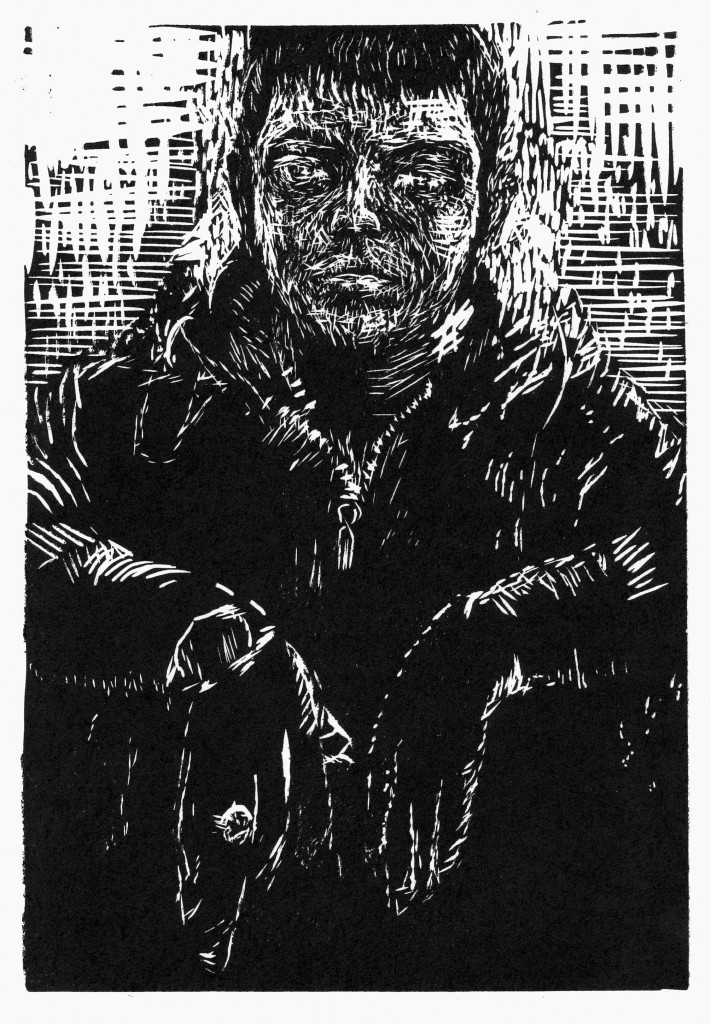

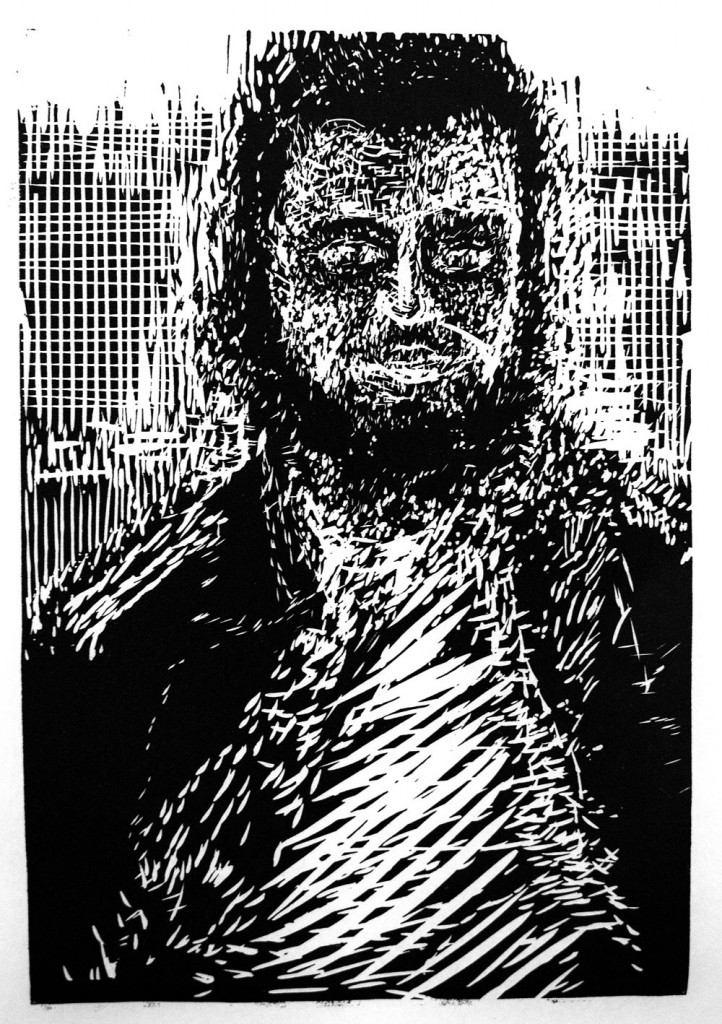

Awad

» I’m from Dara’. I’m a farmer. We belong to the group the others call “Les Miserables” because we have been told we will never be able to walk again.

I’m 20. I was in the Free Syrian Army for a year before I got wounded. We had informers who used to tell us where the National Army was. We had to pay them of course, but in the beginning they gave us good information. With time their information became less and less reliable. Often they lead us into dangerous situations. We went to attack a base. The way there was very difficult and dangerous. When we arrived it was much bigger and better defended than we had expected. There were lots of soldiers. I was shot in the shoulder. The Free Syrian Army brought me to Amman. I thought I would spend 5 days recovering and then return. The bullet affected all my nervous system. I haven’t been able to move since. My situation is hopeless. Look, this is how I was as a fighter (shows photo on mobile phone). Now everybody makes fun of me because they know I can’t do anything on my own anymore. I never imagined something like this could happen to me.«

Lieber Herr Best,

rein zufällig bin ich über die Zeitschrift Diwan auf ihr Kunstprojekt mit syrischen Flüchtlingen in Amman aufmerksam geworden. 2009-2011 war ich für den DAAD als Lektor in Beirut und ich glaube, wir sind uns dort im Rahmen eines Austausches begegnet. Seit 2012 leite ich das DAAD-Büro in Amman und würde mich gerne mal mit Ihnen treffen. Wie lange sind sie denn noch im Lande?

Ich fliege übermorgen und komme am 5.1. wieder. Aus zeitlichen Gründen wird es in diesem Jahr leider nicht mehr klappen, aber vielleicht Anfang Januar?

Mit besten Grüßen

Andreas Wutz

Hallo ihr Lieben!

Denke oft an euch und wünsch euch viel Kraft für die wundervolle Aufgabe, die ihr euch vorgenommen habt!!

Grüße aus Berlin

vom ollen Günter

I’m deeply touched by the pictures and the words. What a great and important project & art!!